2022 economic roundup: inflation top story, pandemic losses recouped but growth still stalled

Statistics Canada’s release this week of national balance sheet accounts — an accounting of our net worth — was one of the final pieces of the economic data puzzle for 2022 and allows us to more or less complete the picture of how the economy and Canadians fared last year. Here’s the recap.

Inflation

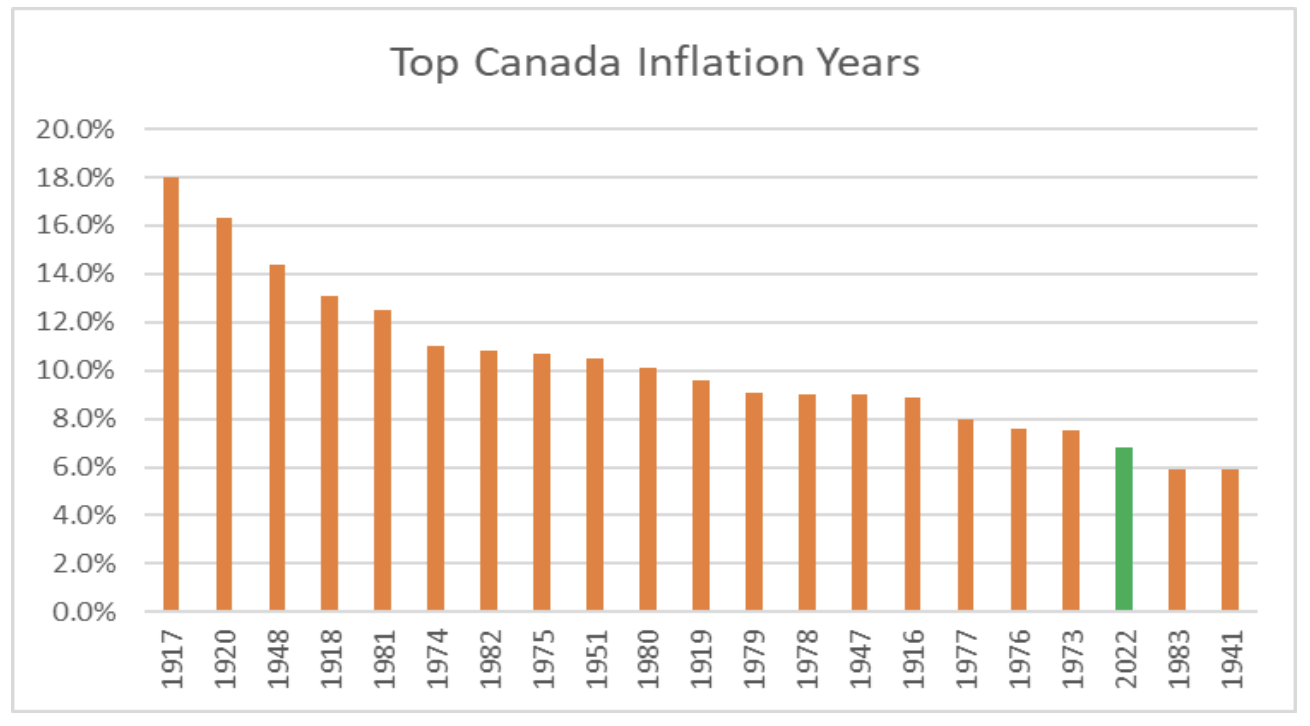

Inflation was — obviously — the big story. It was unexpected in both scope and breadth. Consumer prices rose on average 6.8 per cent in 2022, the biggest increase since 1982. And it felt even worse given the biggest increases were for the basics: transportation, food and shelter.

The initial judgment from policy makers and most economists that it would be mild, benign and short-lived was spectacularly wrong. Which is why the Bank of Canada quickly pivoted and engineered one of the most aggressive interest rate hiking cycles ever — the other big contiguous story of 2022.

Still, Canada’s inflation experience was softer than many other advanced economies; we were hit less by surging energy costs than in Europe. We’ve also seen worse historically, though not in recent memory. Over the past 110 years, 2022 inflation ranked 19th highest — nine of those were in the inflationary crisis stretching from the mid-1970s to the early 1980s.

Business and government

Inflation was great for business profits and government coffers.

According to the pre-tax profit proxy used in gross domestic product accounts, corporate incomes rose nine per cent last year to a record $426 billion and are up 46 per cent since 2019. Revenue taken in by all levels of government was also up by nine per cent to $1.1 trillion and is 21 per cent higher than in 2019. Government receipts are in line with growth in nominal economic activity, which also has been fuelled by rising prices.

But inflation has a tendency to start with laughter and end in tears.

Rising costs and a slowing economy are showing signs of catching up with both business and government. While it was a good year for corporate income, profits peaked in the second quarter, and were down in the second half of the year.

Government revenue growth also showed signs of a slowdown at the end of 2022, even as spending continues to grow at a robust pace — a dangerous combination that doesn’t bode well for the 2023 fiscal picture.

Households

Households didn’t fare as well last year, though Canadians on average still remain much better off financially than they did pre-pandemic.

2022 was one of the worst years ever for worker purchasing power. For example, labour force survey data show that hourly wages increased on average by 4.2 per cent last year, well below the 6.8 per cent increase in consumer prices. That would represent the largest drop in wages when factoring for inflation since at least the late 1990s.

National balance sheet data released this week show a similar picture when it comes to wealth. Household net worth in Canada fell by $743 billion last year to $15.5 trillion. On a per capita basis, the decline was even deeper.

But wealth — in absolute and per capita terms — is well ahead of pre-pandemic levels. Even real wages remain just slightly ahead of where they were in 2019 – despite the pullback in purchasing power last year.

We remain — collectively — better off thanks to the generous COVID-19 government support to households and the surge in home values in 2021 that remains intact despite the recent housing correction. But this pandemic “windfall” is being eroded by inflation and the impacts of rising interest rates.

GDP

Economic output grew at a 3.4 per cent pace in 2022. That’s slightly less than what was expected when economists were looking at the year ahead in late 2021, but still solid. It’s one of the fastest gains of the past two decades and an impressive follow-up to 2021 when the economy expanded by five per cent.

Our pandemic losses have easily been recouped, but many analysts (including Phil Smith here) point out that Canada’s growth track is still well below pre-pandemic trends (i.e. how large the economy would be had the pandemic not happened). But recouping those “counterfactual” losses seems an untenable goal at this point, especially since the economy is expected to stall in 2023.

Labour market

While wages haven’t been keeping up with the rising cost of living, the labour market has been thriving with businesses hiring anyone they can find.

The economy added a net 409,000 jobs in 2022, a 2.1 per cent increase. There have been stronger years but never with the unemployment rate hovering at near-record lows of about five per cent.

Economists will tell you employment is a lagging indicator, but there has been little sign of a slowdown in the first two months of 2023.

Housing

Everyone is familiar with the housing story. After a historic price surged in 2021, benchmark prices peaked early last year and have since been on a sharp decline. According to Canadian Real Estate Association data, prices ended the year 7.5 per cent below the end of 2021. But it’s mostly a new buyer problem. Home prices are still 30 per cent above levels at the end of 2019 — one reason why net wealth remains so elevated vis-à-vis pre-pandemic levels. There are also signs that the recent slide may be troughing out as Canada ramps up immigration levels.

Population

We still don’t have final population estimates for last year, but it’s easily going to be a record. In the first nine months of 2022 alone, Canada’s population increased by 776,217 — already the most in any one year ever.